Of all of the old grimoires, the one that intrigues me the most is called the Grimoire of Armadel. I am intrigued because not much is known about this grimoire, and the class of magickal lore it contains seems to have no peer. It is supposedly associated with an unknown author who bears the mysterious name of “Armadel.” This grimoire has a curious history and an even more enigmatic use. Some occultists have looked through the book in vain for some clue as to how to use it, since the actual text is very terse, obscure and doesn’t make a lot of sense. The lack of any in-depth instructions has made this work rather challenging. One could make the argument that the grimoire either requires the simplest of magickal regimens (such as candles, incense and prayer) or that it’s incomplete. My opinion is somewhere between these two arguments, so that would mean that I believe that there are some parts missing, but there is enough to make it work – as we shall see.

The current edition that is still in print today was published by Weiser in 1995, but a first edition was published in 1980. Prior to that, the manuscript had never been published. Of the two editions, the second has a more thorough introduction, written by William Keith. The first edition had an introduction penned by the late Francis King, but it was less substantive than what William Keith wrote in the second. The original manuscript was translated by Samuel MacGregor Mathers when he was living in Paris, but it was never published during his lifetime. Mather’s translated manuscript was later acquired by Gerald Yorke, and it was only then that it was subsequently published.

There’s also a new book recently out that claims to make full use of this grimoire, called the “Grimoire Armadel Ritual Book” written by Kuriakos. A blurb from the advertisement for this book says the following:

“This Grimoire of Armadel Ritual book is the most powerful and yet simple Magick you will ever do! You only need a candle, bell, rope and incense and 10 minutes to do each ritual.”

Considering that the each of the spirits listed in the grimoire was supposed to be conjured to activate the sigils or characters found in the book (using the classical five step methodology), it would be far too easy if the magickal operations were that accessible or simple to execute. Certainly, if that were the case, others would have already solved the mystery of this grimoire when it first came out thirty years ago. Nevertheless, since I have not read this book, I won’t pass any judgement on it, leaving it to my readers to judge for themselves if they are curious. I have found the various contents of this grimoire to be anything but simple and easy to access, but that’s just my opinion.

Perhaps the first thing that anyone would need to know to penetrate the mystery of the Grimoire of Armadel, at least from the standpoint of the tradition of grimoires, is to know where it came from and when it was originally created. Unlike many other grimoires, there is only one known manuscript copy in the world, which is MS 88, kept in the Bibliotheque l’Arsenal in Paris. The manuscript, written in Latin and French, was probably produced in the early 18th century. The fact that it has such a low catalogue number shouldn’t indicate that it was older than other manuscripts, since the numbering system may or may not indicate a manuscript’s chronological placement in the catalogue. There are over 12,000 manuscripts kept in that library.

The library of the Arsenal in Paris has over a million books and other papers, and even in the late 19th century, it was quite voluminous. Yet of all of the occult books, manuscripts and grimoires to be found in that repository, only two were translated by the occult scholar and founder of the Golden Dawn, Samuel MacGregor Mathers – the Book of Abramelin and the Grimoire Armadel.

In his introduction, William Keith wondered why Mathers bothered translating this work since according to him it was both derivative and a late edition to the various families of grimoires. Did his teachers, the secret chiefs, instruct him to translate this book? No one is now able to answer that question, since Mathers, and all of his immediate associates, have passed away. Yet any occultist or magician can immediately appreciate the importance and power of this grimoire by simply examining it. From a literary perspective, William Keith is probably correct, the Grimoire Armadel did not seem either impressive or particularly revelatory. However, from an occult perspective, it is easy to see why Mathers spent his time translating this manuscript – the sigils and various characters, all in color, are quite astonishing and impressive, even to the lay occultist.

Scrutiny of the manuscript revealed, even to Mathers, that the original grimoire was probably written in German, since there appears to be some word usage and terms that are obviously poorly translated from that language into French (such as Kanssud for Sud Kante – p. 30, Man for One – p. 31, etc.). The chapters have grandiose liturgical titles written in Latin that seem to have little to do with the actual content of the chapter, which typically consists of a short paragraph and either the sigil of a spirit or the enlarged magickal character of some visionary process, or both. Yet the sigils and characters are of a remarkable nature that are not found in any other grimoire, although there are some sigils and characters in other grimoires that might be analogous. However, the names of the various spirits are taken from other grimoires, such as the Heptameron, the Arbatel, Agrippa’s Occult Philosophy and the Grimoire of Pope Honorius. One can easily guess that the Grimoire Armadel came after these books and manuscripts, since it uses the spirit names from these traditional sources. However, the sigils and characters are unique, representing the greater contribution of this work - but the rest was apparently derivative.

The name Armadel should not be confused with other similar names found in the famous grimoire titles of history. There is the Almadel, which is the fourth book of the Lemegeton or Lesser Key of Solomon, and the Arbatel, which is a grimoire of planetary magick derived from the occult teachings of Paracelsus. The name Armadel has no known definition, so it would seem to be a proper name, possibly indicating the name of the author. William Keith cites another grimoire in the arsenal entitled “Armadel’s Grimoire ou la Cabale” (MS 2494) and a grimoire in the British Museum “The True Keys of King Solomon by Armadel” (Landsdowne MS. 1202), both of these manuscripts contain the name “Armadel” although there is no clue as to the identity of this individual - he is not an obvious historical person.

Originally, I had assumed that the name Armadel was of Hebrew derivation, but the closest I could come to the actual name was ORAM-MAD-EL, or God’s Mighty Wisdom. Other authors have considered that the name Armadel was a variation of Almadel, but I disagree. I think that they are distinct, since Almadel incorporates skrying, and Armadel performs extended conjurations with sigil characters to induce visions and obtain knowledge. As I have said, I believe that the name Armadel is probably a proper name.

According to William Keith in his introduction (p. 11), the name Armadel is referenced in a book listing occult books and manuscripts, written by Gabriel Naude in 1625. In that bibliographical book on occult works, Gabriel states that there are five basic categories for the practice of the magickal arts, and except for one, these were documented classes of literature well known to the occult literati of the time:

- Trithemius - art of invention,

- Theurgy - art of elocution,

- Armadel - art of disposition,

- Pauline - art of pronunciation,

- Lullian - art of memory.

Of course, all but Armadel represent a verifiable literary source for the magickal arts; yet it would seem that back in the early 17th century the “art of disposition” was an important magickal practice. We must thoroughly examine the contents of the grimoire and compare it to other works if we wish to fully comprehend what is meant by the art of disposition.

“The Grimoire of Armadel claims to conjure spirits that (judging from their descriptions) affect the disposition of the magician, rather than grant specific powers or perform definitive duties, as do spirits in other grimoires,” so states William Keith. However, the kinds of operations that this grimoire performs appear to involve the gaining of knowledge, wisdom, deep mystical insights and even a kind of enlightenment. That type of magick was considered the “art of disposition, ” according to various obscure references, and it was believed to be a form of magick that had the greatest effect on the individual practitioner, granting him or her a kind of gnostic wisdom or illumination. Certainly, this particular practice in the art of magick would have been greatly admired in its time, only to be obscured and then superceded by the more grandiose types of material based magick, such as those found in forms of angelic, talismanic and goetic magick.

Another grimoire that might be considered similar to the Grimoire of Armadel would be the Notary Art of Solomon, or the Ars Notaria, as it was called. It was supposed to be the fifth book of the Lemegeton (Lesser Key of Solomon), but it’s usually excluded because no version or published book has been able to capture the incredibly intricate and beautiful illuminated characters and sigils (notae) that fill up whole pages, formed from the calligraphy of various strange words of invocation. The purpose of the words of invocation and the notary devices was to assist the wielder to acquire certain spiritual and occult knowledge directly, without the outer apparatus of learning. It would seem, then, that this grimoire, which has been dated to at least the early or middle 13th century (and is actually independent of the Lemegeton), would be of the same class of grimoires as the Grimoire of Armadel. Both manuscripts claimed to instruct and assist the operator in a form of magick that would powerfully impact his mind, revealing hidden and occultic wisdom – thus they were grimoires of the art of disposition.

There are probably other grimoires in various collections and libraries that could be classified as belonging to the magickal art of disposition. One could easily categorize a lot of the higher ritual magick that I work as belonging to this category, making it probably one of the most important of all of the categories of magick that are practiced in the Order. At some point in the career of the magician, there is a noticeable shift from working magick to exclusively achieve material objectives to acquring hidden knowledge, wisdom, and ultimately, enlightenment. Some never make that transition, and others seek it without having the solid base of the mastery of practical magick. However, the art of magick that is used to gain knowledge, wisdom and enlightenment is the art of disposition.

Additionally, I have assumed that the Grimoire of Armadel was part of a family of grimoires that originally came from Germany, representing a group of books on magick as profound and famous as the Book of Abramelin, Sepher Raziel, the Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses and the Grimoire of Pope Honorius. Where it fits into that tradition will only be determined when a German original is found, or at least other versions of the same Grimoire. I have already done a little bit of research and writing on this grimoire manuscript in my article on the Old Grimoires (as of yet unpublished). I have decided to quote a paragraph or two to share what I have discovered.

“The Grimoire of Armadel also comes from this [German] tradition, but only a poor Latin and French edition was available to Mathers for translating, and much later printing. We can hopefully anticipate the eventual discovery and publishing of a more fresh translation from a currently unknown German version. However, few have ever gazed upon the sigils and characters found in the Grimoire of Armadel and not marveled at them, even though the ritual lore to activate them is extremely sparse, and there seems to be no way to actually use any of the sigils and characters (without recourse to other materials). The Grimoire Armadel probably has its origins in the late 17th to early 18th century, and represents the last flowering of this tradition.

Owen Davies, in his book (Grimoires - A History of Magic Books - p. 97), has speculated that the Armadel manuscript may have been part of a collection of hundreds of confiscated magical books held for safe keeping by the lieutenant general of the Paris Police force, Marc-René de Voyer d’Argenson, who was investigating the massive occurrence of occult fraud in Paris in the early 18th century. These grimoires found their way into the library of his grandson, Marc-René, 3rd marquis d'Argenson, whose huge collection of books was purchased by the King’s brother (Count of Artois) in 1785 and became part of the famous Bibliotheque l’Arsenal of Paris. Eventually, the grimoire was discovered languishing in that manuscript collection over a century later by Mathers, who immediately saw its value and translated it.”

The idea that the Grimoire of Armadel had been confiscated from some cunning man or sorcerer for hire in Paris in the early 18th century is quite intriguing. Who originally owned the manuscript, how was it produced and where did it come from? These questions will never be answered. Since there are some references to the name Armadel in the 17th century, then it would seem likely that the grimoire was produced sometime anywhere from the mid to the late 17th century, so it wasn’t actually as recent a work as it might have seemed, yet it was produced later in time than other classic grimoires. This should not devalue the importance of this book, since it can be reasonably shown to be part of a historical context that occurred at the height of the great age of grimoires. Where the 16th century established the foundation of the tradition of ceremonial magick, the 17th century saw it become refined and developed into a form that we would recognize today. Most of the grimoire manuscripts that exist in libraries in the present era are from the 18th century or later, when such books were copied and translated as a sort of clandestine industry for wealthy collectors and amateur practitioners.

An examination of the Grimoire of Armadel shows that it suffers from some disorganization, since the chapters follow no observable order. In fact the title page in the original manuscript is at the end instead of the beginning, leading some to speculate that perhaps the book was written from back to front. However, the order of chapters for the first two chapter groups is not important, since each of them can stand alone with their associated spirit name and sigil, offering revelations and visions with their use that are unique and distinct. The broader chapter group sections could be considered separate books whose titles consist of the words “theosophy”, “sacro-mystic theology” and “qabalistical light,” obviously characterizing the presentation of arcane occult knowledge associated with various mysteries of the Bible. Most of the chapters are concerned with highly obscure Old Testament mysteries, but there are some New Testament mysteries presented as well.

It has been said that this grimoire is somehow more Christian than other grimoires, but I find that opinion to be superficial, since there are many grimoires that are Christian based, such as the Ars Notaria, Liber Juratus, Arbatel, Grimoire of Pope Honorius and numerous others. The infusion of Qabbalistic concepts into this grimoire would show that it had a blending of Jewish and Christian elements, but like many of the grimoires from that time it was produced by and for Christian ceremonial magicians. One could also assume that the would-be practitioner engaged in special rites of purification, atonement, and receiving the sacraments of the Mass, although this is not specifically stated. However, seeking the protection of Saint Andrew and Saint Thomas and the obscure references to a “Misterium Stile” would seem to indicate that the sacraments and blessings of a Catholic liturgy would characterize the spiritual background for this working.

The array of spirits found in this grimoire demonstrates the varied mixture of traditions that were plumbed to fashion it. They are associated with the ten Sephiroth, the Olympic spirits of the Arbatel (omitting Hagith – Venus), and include the addition of four of the planetary archangels found in Agrippa’s Occult Philosophy. There are also spirits associated with the Hebrew letters, from Aleph to Tet (for the numbers 1through 9) and two previously unknown archangels. In addition, sigil characters are found for five infernal princes, Mephistopheles (spelled Hemostopile), and two possibly unidentified goetic demons (for a total of eight altogether). The operator is instructed to steadfastly refuse to be seduced or deceived by the infernal spirits, seeking only to achieve the knowledge associated with the sigil characters. It is interesting to note that the archangels listed in the first book also number eight, and they may have been used in conjunction with the eight demonic spirits, functioning as a type of magickal controlling device. In all, there are thirty-seven spirits, not including the three groups of spirits associated with the Paths of Wisdom, which would then combine to make the mystic number of 40.

Five demon princes listed in the grimoire may have been culled from the Grimoire of Pope Honorius, which was a German grimoire dated from the early 17th century. Mephistopheles would also fit into the context of German grimoires, most notably, the Faustian branch. The demons Brufor and Laune are of unknown derivation, but Brufor could possibly be Brulefer, which was a demon found in the Grimoirum Verum. Most of these demonic spirit names demonstrate an ultimate German context for the Grimoire Armadel.

There are also three sigil characters for the spirits of the paths of Force and Counsel, Joy and Love and Charity (Paths of Wisdom). It would seem that these sigil characters are used to consecrate the altar and magickal tools with some kind of empowered chrism, but the directions are torturously obscure. The rest of the sigils and sigil characters are associated with one or more spirit and some mystery or vision.

Since all of the spirit names are taken from other magickal traditions, it would seem that a simple activation of this system would likely require the invocation of the spirit and the inclusion of the special sigil or sigil character, acting as a mechanism to aid the magician in acquiring some extended vision or specific occult knowledge. Thus the operator would have been required to be knowledgeable and have in his possession copies of the Heptameron, the Arbatel and the four books of Occult Philosophy of Agrippa. The magician would very likely perform invocations of these spirits and have access to them before actually activating the sigils and sigil characters of this grimoire, although this is speculation on my part – the invocations may have been performed as part of the working. The magician would also have been expected to know the Bible in a very intimate manner, perhaps indicating that possessing a printed copy of the Bible would also have been a requirement for this system of magick. This fact would have also determined the location of the source of the grimoire as Germany (or possibly England or the Netherlands), since mainstream Catholics were forbidden from owning or reading the Bible, unless they were clerics or church doctors.

The actual sequence of operational steps associated with this grimoire are somewhat difficult to fathom, since the layout of the chapters appears to be jumbled and out of sequence. However, since the title page is at the end of the manuscript instead of the beginning, one could consider this as a clue to the actual operational sequence of the grimoire. As noted previously, a few critics have said that the order of the chapters is completely reversed, with the ending chapter actually the first chapter, and there is some merit to this speculation. However, it’s overly simplistic to just reverse the order of the chapters, but I believe that a careful examination can readily reveal the actual operational sequence. The following sequence of chapters is based upon my own analysis and should not be considered the final word. (The sequence of operational steps would be called the “Rational Table or Qabalistic Light.”)

1. Characters of Michael - basic preparations – fasting, initial prayers, special considerations.

2. First Character - where the operator fuses himself into the working by applying his initials to a character that is produced on parchment and worn under his vestments near his heart, acting as a kind of phylactery.

3. Vision of Dust - (Raphael and Pelech as Jesus) – possible reference to the receiving of sacraments as a means of establishing a high degree of piety.

4. Vision of Anointing – possible reference to the purity of one’s self and personal consecration.

5. Concerning the Paths of Wisdom – consecration of the temple, vestments and tools. (These sigil characters are used to aid the magician in achieving the grace necessary to perform the work – extracted from the end of Book II)

6. Preparation of the Soul – parts 1 and 2 – consecration of the magick circle. (One would have to borrow an example from some other grimoire, since there is no image of what that magick circle would look like.)

7. Conjurations – first and second, and the license to depart.

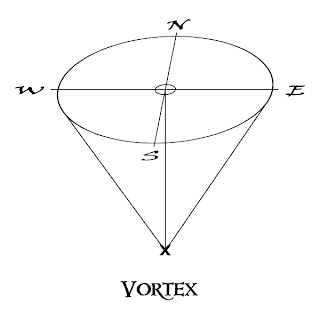

In addition, there is a character sigil for the operation of Uriel Seraphim, which would seem to be the foundational operation for the working. This character sigil is found at the very beginning of the book, before the introduction – there is no accompanying text to reveal its purpose or use. Perhaps this indicates that Uriel Seraphim is the key to this system of magick, and that the magician should invoke Uriel Seraphim using this combination of character sigils. There are also sigil characters representing the other seven archangels found in the first and second books (yet the sigils are different than what is displayed in those books), so these would also be included. It may be that this large array of sigil characters, with a triangle in the lower center, would have been possibly placed in the center of the magick circle, acting as a powerful protecting and empowering mechanism. There are also words of power or evocation placed on both sides of the triangle. The one on the left uses the archangel name Michael, and the one on the right, Gabriel.

Once these items have been performed and established, the magician could proceed through the various operations involving all of the other spirits in the grimoire, beginning first with book 1, the “Theosophy of Our Forefathers” and proceeding through book 2, the “Sacro-mystic Theology of Our Forefathers.” I would assume that each sigil character would be operationally activated only after the spirit had been properly invoked, using the system outlined by Agrippa’s 4th Book of Occult Philosophy and found in the directions contained in the Arbatel. I would also assume that the magician would not actively invoke either the infernal princes or the goetic spirits, using instead the power of the “seraphim” Uriel and the eight archangels to aid in the revelation of these spirits.

Special notice can be given to the fact that the normal operational steps of constraining and binding the spirit are omitted. It is my opinion that since a classical invocation has already been performed, these steps would not be required to activate the sigil characters.

Another minor anomaly is that the name of the archangel Gabriel is shown in the grimoire three times. The archangel Michael is shown twice, as is Zadkiel and Samael. Yet all of the sigils or characters used in the repetitions are different. Gabriel and Michael also appear in the operation of Uriel Seraphim, their unique sigils are shown with five other archangels and their names are used in the left and right hand words of evocation. There is also a parenthetical clue placed under the name of Gabriel, appearing as the central archangel, with the word “oriens” (East?) indicated below it. What all of these anomalies signify is unknown, but it would seem that Gabriel, Michael and Uriel may play key roles in the operation of the grimoire. Another note, the archangels Caphael and Thavael are unique to the Grimoire of Armadel – they are not found in any of the angelic lore or literature.

Finally, I have found in the grimoire an odd association with Jesus and the name “Pelech.” After looking over various possible Hebrew words, I have determined that the word Pelech is very likely the Hebrew word “Pelach,” which is the masculine pronoun from the verb root PLCh, which means to be sliced or broken apart. This association, in my opinion, represents the aspect of Jesus Christ as the sacramental wafer of the Eucharist as well as the Crucifixion. (It might also indicate some alchemical operation.) So it would seem that my guess about the chapter entitled the “Vision of Dust” is a very obscure reference to receiving the sacraments, specifically the host of the Eucharist. I would also suspect that such an oblique reference might symbolize that the host should be used in the magick circle, to fortify and amplify the sacral power of the working. The obscure wording could be justified if it was meant to protect the operator from being accused of performing diabolical ceremonial magick, or at the very least, committing sacrilege.

To recap: the Grimoire of Armadel is a very peculiar manuscript of ceremonial magick. An analysis of its various chapter components has revealed that the operational sequence was deliberately made obscure. This grimoire requires the knowledge and use of other grimoires, most notably the Heptrameron, Agrippa’s Occult Philosophy and the Arbatel. The key to operationally using this grimoire requires re-establishing the operational sequence and also performing classical invocations of the various spirits before performing the sigil character operations. The art of Armadel appears to be a system of magick that assists the operator in acquiring visions, insights, occult knowledge, wisdom, and ultimately, spiritual enlightenment. It is a system of magick that can be found in other systems of magick where spiritual knowledge is considered more important and personally empowering than material powers and achievements.

While I was still in the process of examining this grimoire, I did make use of the three sigil characters of the Paths of Wisdom many years ago, and have found them to be extraordinarily powerful and very useful. They are used to adorn the gateway keys that I use in the performance of ritual magick. As time goes on, other parts of the grimoire will be incorporated into the ritual system of the Order as well. Since I have determined the actual operational steps and the requirements for making this grimoire fully functional, I need only to build a system of magick to use the special sigil characters.

Once I have activated these sigils and characters, I will likely find that their impact upon my conscious mind will produce a very different result than what is described in this grimoire. It will give me the insight and wisdom to write my own Gnostic pagan version of this obviously Christian grimoire. I might want to use the Gnostic books of the Apocryphon of John and the Trimorphic Protenoia as the spiritual background for this new grimoire, since they are personally important to me and to the Order. Religions and creeds may differ, but the over-arching spiritual wisdom contained in these sigil characters goes far beyond the tenets of any one specific religious perspective. As they are part of the spiritual and cultural matrix of the Western Mystery Tradition, they are also accessible to one and all.